Post by Brett Peto

This article appears in the winter 2024 issue of Horizons, the award-winning quarterly magazine of the Lake County Forest Preserves in northern Illinois.

Ice seems temporary. It melts in a glass. It disappears at a sunbeam’s touch. It ebbs with the first relief of spring. But some ice leaves deeper marks than a cold drink.

On the banks of the Fox River in the southwestern corner of Lake County, Illinois, you can see back through time. Not long ago on the 4.5-billion-year arc of Earth’s history, a wall of ice 700–2,000 feet tall covered everything in view today. There was no wide, shallow river. No trees or flowers. Only ice.

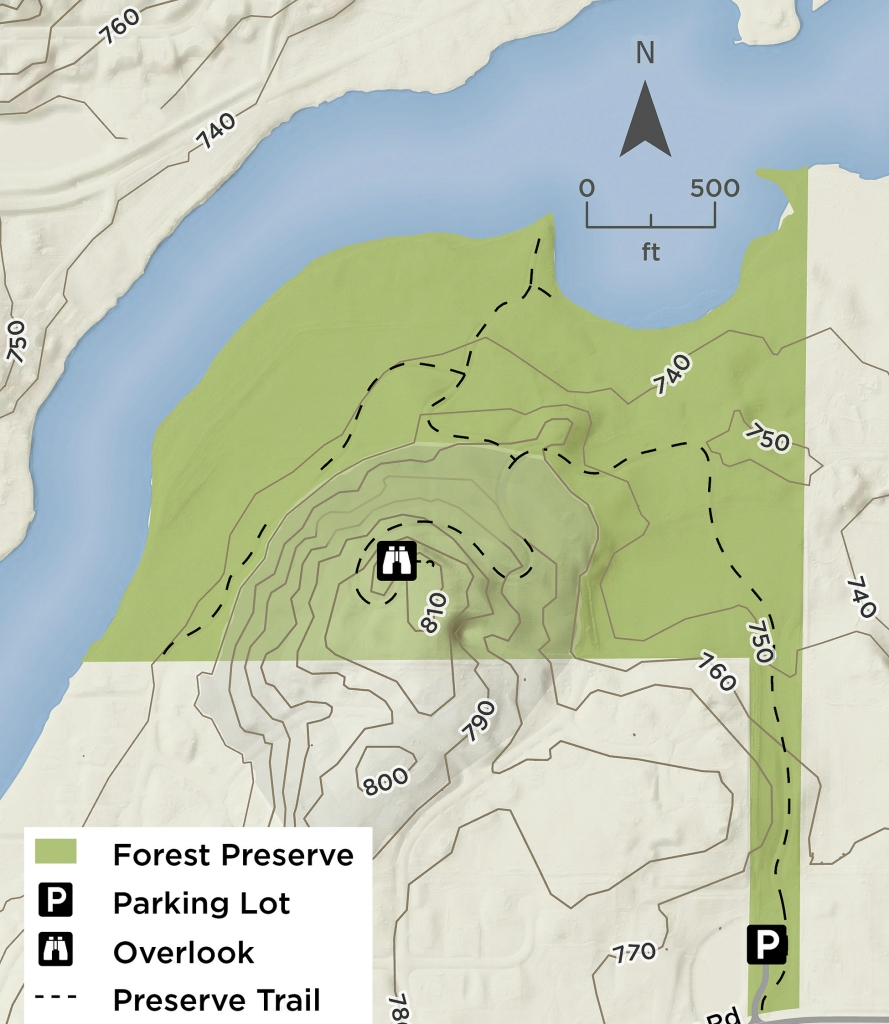

Today, 691 acres near the river’s eastern shore make up Grassy Lake Forest Preserve in Lake Barrington. The preserve features 5.6 miles of trails, six scenic overlooks, sedge meadows and mature oak woodlands. Set back less than a quarter mile from the low, forested riverfront is what looks like a medium-sized hill.

A 1.6-mile trail makes a half-spiral as it ascends the hill to an overlook with magnificent views of the Fox River. There, you can rest on a bench, watch the water flow by and ponder this …

You’re sitting on a gift from the glaciers.

Catching the Drift

Starting 2.58 million years ago during the last Ice Age, a massive continental glacier called the Laurentide Ice Sheet formed near the Arctic Circle. It enveloped millions of square miles, blanketing most of what would become Canada and the northern U.S.

Like waves crashing onto a beach, the ice sheet grew and retreated over the land in cycles lasting tens of thousands of years. The area that’s now Illinois experienced three major glacial periods: the Pre-Illinoian Stage, the Illinoian Stage and the Wisconsin Glacial Episode.

As the Laurentide advanced, it pulverized rock, silt, gravel, sand and sediment, carrying it for miles and depositing it elsewhere. Known as drift, this mixture is widespread across Chicagoland.

The Laurentide’s final southward expansion occurred around 95,000 years ago. Its departure from Illinois between 10,000–12,000 years ago leveled off many of the state’s former bluffs, valleys and hills into today’s largely flat landscape.

The Mississippi River once ran through central Illinois, until the ice sheet pushed the waterway west to its current course. The modern Illinois River follows the Mississippi’s prehistoric path.

A time capsule of pre-glacial topography exists in the Driftless Area, a region spanning portions of southwestern Wisconsin, southeastern Minnesota, northeastern Iowa and northwestern Illinois. Ice didn’t cover the Driftless. This left intact cold-water trout streams, rugged hills, caves, waterfalls and other striking features that are rare in Illinois.

Kames and Kettles

Clues to Lake County’s icy past are still visible. “Lake Michigan, the Fox River and the Des Plaines River were all left behind by the Ice Age,” said Public Program Specialist April Vaos. The medium-sized hill at Grassy Lake is an example of a kame.

“A kame is formed when a glacier cracks and allows water to pool and pile sediment,” Vaos said. “Once the glacier melts, a mound of gravel and sand is left in its place, creating this kame, or what people see as a hill.”

Kettle lakes dot the county, too. They started as chunks of ice left behind by a retreating glacier. “Eventually soil buried them, and as they melted, they created circular lakes called kettle lakes. It’s neat to look at maps of Lake County and notice these lakes.”

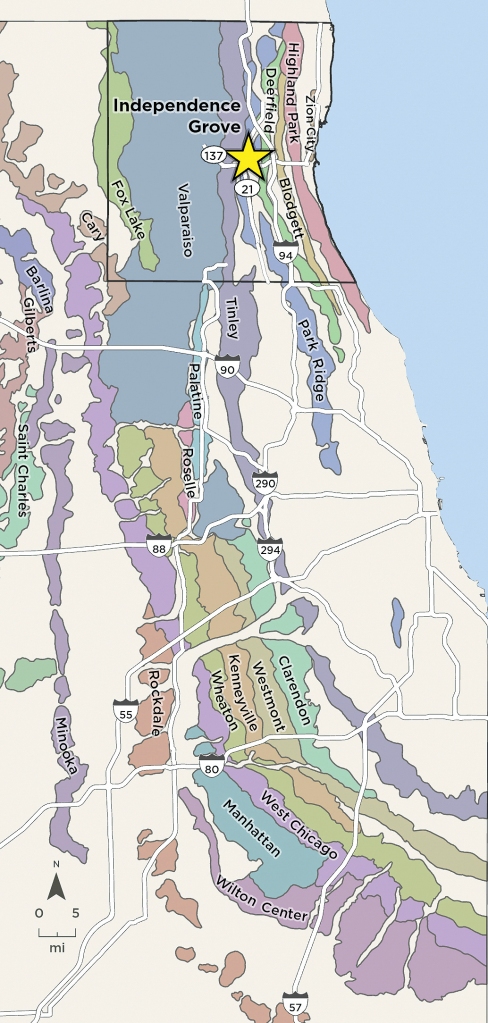

Recessional moraines are another glacial feature present today. They’re low ridges formed by a glacier pausing and depositing more sediment in one place. A portion of the Valparaiso Moraine rises west of Independence Grove Forest Preserve in Libertyville near Illinois Routes 137 and 21.

“If you leave out of the preserve entrance and look to the west, you’ll see a hill going up on Route 137 toward Route 21. Folks may not realize this is a great example of a moraine,” said Vaos.

Water east of the Valparaiso Moraine generally flows into Lake Michigan and through other Great Lakes into the St. Lawrence River and eventually the Atlantic Ocean.

Water west of the moraine heads to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. An exception is the Des Plaines River. The top of the moraine is west of the river, but the water flows into the Mississippi.

Illinois is called the Prairie State now. But this land has a longer memory.

“Illinois was once a warm, tropical ocean with shelled creatures called crinoids. It was a delta swamp at one point. It was an arctic tundra during the Ice Age and had animals we couldn’t imagine today,” Vaos said.

Visit the Dunn Museum in Libertyville to learn about prehistoric Lake County.

A Great Lake

East of the Driftless Area and the Mississippi River, the Laurentide also carved gigantic basins totaling tens of thousands of square miles. Some portions plummeted more than 1,000 feet down. The ice thawed. Its meltwater created the Great Lakes.

According to the Great Lakes Commission (GLC), an interstate agency, Lakes Michigan, Superior, Huron, Erie and Ontario “cover more than 94,000 square miles and hold an estimated six quadrillion gallons of water.”

That equals more than 9 billion Olympic-size swimming pools.

The Great Lakes are Earth’s second-largest source of fresh surface water and account for 90% of the U.S. supply. The eastern edge of Lake County has more than 20 miles of shoreline on Lake Michigan, “the only Great Lake entirely within the United States,” the GLC wrote.

“Approximately 118 miles wide and 307 miles long, Lake Michigan has more than 1,600 miles of shoreline. Averaging 279 feet in depth, the lake reaches 925 feet at its deepest point.”

Each day, the City of Chicago’s Department of Water Management “purifies and delivers approximately 750 million gallons of drinking water to residents of Chicago and 120 suburbs. 42% of the whole state gets their water” from the department.

Lake County draws its drinking water from Lake Michigan and groundwater aquifers. Aquifers are underground layers of permeable rock or sediment that act as natural storage for water.

By appearances, Lake Michigan is a steady presence, an anchor for the northeastern corner of Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana and Michigan. Yet the lake is not invincible.

A Vulnerable Lake

It looks like a scene from Minnesota, Manitoba or Alaska. Shelves of ice cluster along the shoreline. Waves carve little caverns into them, icicles smattered with sand hanging from their ceilings. Miniature icebergs with eccentric rings of frozen froth idle offshore.

With about two miles of shoreline, Fort Sheridan Forest Preserve in Lake Forest has a front-row view of Lake Michigan’s winter ice.

The 321-acre preserve contains 3.65 miles of trails, six ravines and rolling coastal bluffs home to plants that are rare farther inland. More than 140 species of birds rest and refuel here during spring and fall migration.

For human visitors, an accessible overlook atop a 70-foot-high bluff reveals the blue oasis of the lake. During winter, a crust of ice normally freezes near the shore.

Last winter, not so much.

On February 11, 2024, ice covered only 2.6% of Lake Michigan’s surface area. The Great Lakes totaled 12.18% on February 19 before falling to 4.3% on February 26. Historically, Great Lakes ice coverage usually peaks at 40% or more in late February and early March.

That’s according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL). Since GLERL’s satellite-based measurements began in 1973, “annual maximum ice coverage has decreased by approximately 5% per decade.”

Climate change is a major contributor. Illinois’ average daily temperature has risen 1–2 degrees Fahrenheit over the past 120 years, said Illinois State Climatologist Dr. Trent Ford. “Every season has gotten warmer and wetter. It’s consistent across the state.

“Winter has warmed at a much faster rate than summer. When we break down winter, the most extreme daily temperatures have warmed faster than the more moderate temperatures. For example, we’re getting many fewer minus 10 or 15-degree days than we are 5 or 10-degree days.”

“Every season has gotten warmer and wetter. It’s consistent across the state. Winter has warmed at a much faster rate than summer.”

Dr. Trent Ford, Illinois State climatologist

The Price of Less Ice

Present-day ice is just as important to Lake County’s landscape as prehistoric ice was.

Lake Michigan’s seasonal ice shelf provides armor for coastal infrastructure and natural areas such as Fort Sheridan against strong winds and waves. It also offers some fish species “protection from predators during spawning season,” GLERL wrote, and reduces how much water evaporates into the atmosphere.

Thinner ice coverage allows shipping lanes on the lake to stay open longer, increasing shoreline erosion. Waves strip away sand, stone and vegetation. Infrastructure such as seawalls can help mitigate that. But endlessly reinforcing them while trucking in sand to restock dwindling bluffs and beaches is not sustainable.

In 2020, the Forest Preserves and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Chicago District tried a different approach. A contractor built several underwater reefs parallel to Fort Sheridan’s lakeshore. Made from limestone slabs, tree trunks and branches, boulders and cobblestones, the reefs steer sand toward the shore from their sunken positions 10–13 feet below the surface.

The reefs also create habitat for fish and common mudpuppies (Necturus maculosus), a species of aquatic salamander. The Army Corps is maintaining the reefs through 2025. That includes monitoring the animal populations congregating around them.

We aren’t alone in doing this type of work. In September, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources completed a $73 million shoreline stabilization project at Illinois Beach State Park in Zion. It involved building 22 offshore breakwaters to buffer the park’s 6.5 miles of shoreline, which had been eroding more than 100 feet per year.

These projects make sense for each site. But reefs are not a cure-all. Installing similar structures along all 1,600-plus miles of Lake Michigan shoreline isn’t realistic.

A more proactive approach to protecting the long-term health of the lake, the county and the planet is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and sequester carbon already in the atmosphere. Planting trees, protecting and expanding wetlands and restoring prairies are all good ways to make a difference. Lake Michigan is bigger than your forest preserves.

But we can all do our part to preserve the legacy and future of ice in Lake County.

This feature is adapted from season 3 of Words of the Woods, the Forest Preserves’ award-winning podcast. Listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you prefer.

Images © Mike Borkowski, Jeff Goldberg, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Chicago District. Map sources: ISGS, Esri, Ice Age Mapper, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., Lake County GIS Division, NOAA.