John Page was born in the West Riding, a proud Yorkshireman and was taught to play cricket left-handed “ ’cos it flummoxes t’ bowler, and buggers up t’ field.” He went to university in London and Leeds, and enjoyed (most of the time) attempting to teach young people that there’s a big wide world beyond the Colne and Worth Valleys. He also taught future captains of industry and government at the United World College of SE Asia in Singapore for four years. Except Antarctica, John has travelled and climbed extensively on all the world’s continents, with friends and with Hil, his wife of 44 years. Still very active in his seventies, retirement from paid employment was the best career move that he ever made.

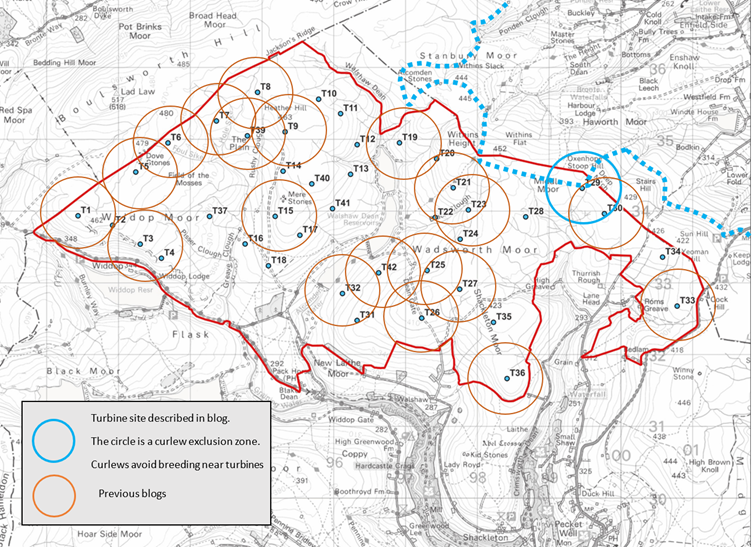

Turbine 29 Oxenhope Stoop SD 99467 34296 ///hiker.curable.lately

July 9 2025 I had a wonderful day out with some good friends walking the Emily Brontë 15-mile circular walk from Oxenhope, using the route description from Michael Stewart’s excellent book Walking the Invisible, a collection of Brontë-themed walks with lovely maps by Chris Goddard, last seen here running to White Swamp in the winter of 2024. The walk showcases this corner of the West Riding at its very best, especially on a bright sunny day in early July. The weather is not always benign. Part of this circular walk follows the route of the Crow Hill bog burst, a vast peat slide in 1824 on the ground that the Calderdale Energy Park (CEP) Option B Access must cross, and this will be our focus. The bog burst happened while Anne and Emily Brontë were walking on the moor in a storm. They had descended to Ponden and were sheltering in the porch of a farmhouse when Stanbury Bog above them exploded, and the vast peat slide poured past.

We make our way out of Oxenhope by a very low Leeming Reservoir.

Eventually we are on Nab Hill, right under Ovenden Moor Wind Farm, where we search out Simon Armitage’s thoughtful poem, Mist.

We take our first breather. Another septuagenarian, Ashley, points out his old lorry driving base at Leeds-Bradford Airport, 30 km away across the densely populated Bradford conurbation. Brontë Country is the back yard of a million people living in some of the most deprived towns and cities in England.

It’s easy along the Yorkshire Water conduit and we are soon on the Oxenhope Stoop plateau.

At Top Withins we engaged with a visiting German family (from the Bodensee area) about the proposed wind farm. They were flabbergasted, as was a local runner from Siddal in Halifax whose colourful use of Old English expressed the feelings of many people, near and far, who understand CEP as simple greed.

From Top Withins it is a stroll up the desire path to the trig point, Alcomden Stones and Emily’s unmitigated moor. From the stones it seems an easy walk to Crow Hill across Stanbury Bog, but such are the difficulties on this quaking ground that even Chris Goddard shows no path in his guide book.

Michael Stewart’s route goes down from the Alcomden Stones to below Ponden Kirk, where you might find the interesting carved stone above. The path follows the line of new shooting butts in Middle Moor clough. The grouse are driven across the moor above. Their heather-skimming flight makes them safe from predators, but at the clough the ground drops away and the guns have a moment to shoot them before they find the safety of the far side. It is the difficulty of the shot that makes grouse such a high-status target that a grouse moor is valued at £3000 per brace. The grit boxes and water trays, found all over the moor and marked by white stakes, service a single brace and their chicks. For such a large bird, grouse are naturally short-lived, typically three years. The guns shoot a calculated surplus in August that would otherwise die in the winter. Curlews by contrast live for thirty years. When assessing curlew breeding success in an area, it is vital to count fledglings. Adults might return to a heavily-predated nesting site for thirty years, lay 120 eggs in total, and raise few if any fledglings.

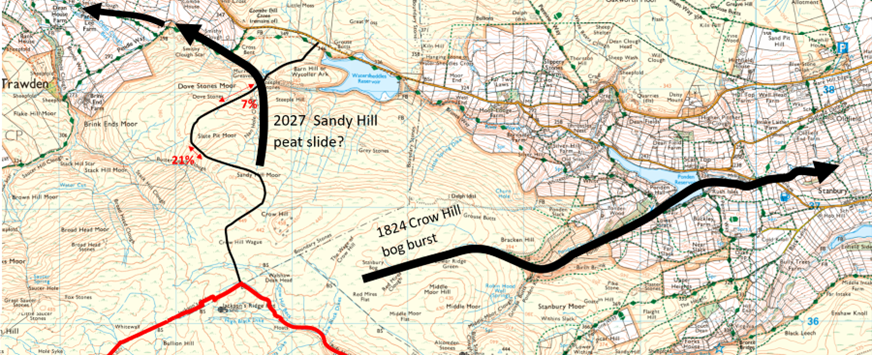

Now we are in the track of the bog burst, which happened in a storm on 2 September 1824. Understanding the bog burst is crucial to the assessment of the Option B access to Calderdale Energy Park, and to the way the development fans out from the huge compound that would be flattened on Jackson’s Ridge.

Anne (4) and Emily Brontë (6) had walked five miles from home when the bog exploded with such force that the bang was heard in Leeds. Their father Patrick heard it in Haworth and had to see out the storm at the Parsonage, not knowing if his young children would return from the moor with their helpers Nancy and Sarah Gerrs. Patrick Brontë based his next sermon on this earthquake.

“A rapid torrent of mud and water issued forth, varying from twenty to thirty yards in width and four to five in depth; which, in its course for six or seven miles, entirely threw down or made breaches in several stone and wooden bridges – uprooted trees – laid prostrate walls – and gave many other awful proofs, that, in the hand of Omnipotence, it was an irresistible instrument to execute his justice.

Sometimes, God produces earthquakes as awful monitors to turn sinners from the error of their ways, and as solemn forerunners of that last and greatest day, when the universal frame of nature shall tremble, and break and dissolve.”

I was on the other side of Stanbury Bog earlier in the month, beginning research on the snaking track that consultant Donald Mackay proposes to build up to Jackson’s Ridge, the Option B of Calderdale Energy Park. The bog is an intimidating maze of groughs and hags in five-metre-deep peat. This was the source of the bog burst.

At its peak, this torrent was seven feet high and large boulders were picked up and hurled through the air. The devastation can still be seen on the scarred and cratered moors today. For weeks afterwards, the streams were full of dead fish. Ann Dinsdale, Principal Curator at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, narrates a short film of the event.

The following year in 1825 The Edinburgh Journal of Science published an article by David Brewster in which reference is made to the bog burst.

“Reports from Kelso, Berwick, Belford, Newcastle, and many places in Yorkshire and Northumberland, give accounts of a most alarming storm of thunder and lightning having occurred, accompanied with a’ vast quantity of rain, and spreading destruction over a great extent of the country.—Many men and domestic animals were killed by the lightning. It was during this storm that the subterraneous bog burst at Keighley in Yorkshire, which may be traced to the torrents of rain that seem to have accompanied the contemporaneous storm.”

Prior to the bog burst a period of high temperatures and dry conditions were followed by several days of exceptionally heavy rain. This would have led to a very large build-up of water in a dry Stanbury Bog, creating extremely unstable conditions in the deep peat overlaying the sedimentary bedrock. A slippery shear plane formed between the contrasting peat and sandstone, causing the deep peat to slide down the convex slope. Ponden Reservoir wasn’t finally completed (as a compensation reservoir) until 1875 and the vast flow continued unimpeded. The reservoir engineers (Walker and Taylor of Crewe) for the Keighley Water Works Board would know all about this when they built Watersheddles and Ponden Reservoirs and incorporated “slow the flow” mitigation measures into the overall design.

Bog bursts are not uncommon. The Irish Peatland Conservation Council wrote this:

“Bog bursts” or peat flows are a dramatic form of peat erosion. Sections of peat on sloped areas can break off from the main body of a blanket bog and flow down-slope, similar to a volcanic lava flow. Bog bursts usually happen after heavy rain on sites which have been put under human pressures, such as overgrazing, turf cutting or wind farm construction. For example, the construction of a wind farm at Derry Brien, Co. Galway, resulted in a large bog burst causing almost half a square km of blanket bog to travel 2.5 km (Lindsay and Bragg, 2005). During a bog burst it is thought that the living plant layer of the bog tears due to stress and the very wet peat centre flows under the influence of gravity. Other bog bursts have been recorded in Ben Gorm in Connemara, on Clare Island in Co. Mayo and 52 separate bog bursts were recorded at Pollatomish, Co. Mayo.”

Given that CWF Ltd presented such an unfinished proposal at their public consultation, we can have no confidence at all that any thought has gone into the potential for catastrophic peat slides on the north side of CEP.

This history and geology of the 1824 bog burst is crucial for CEP because there are the same geomorphological conditions to the north of Crow Hill Wague, in the catchment of the headwaters of the unnamed streams which flow down to Watersheddles Reservoir. A repeat of the September 1824 bog burst on the top of the convex Sandy Hill Moor slope would wash away the new road, and fan out over Steeple Hill to clog up the small gorge leading into Watersheddles Reservoir, and very possibly large parts of the adjacent Nan Hole Clough. If the mudslide were to follow the Nan Hole Clough valley then Wycoller could be severely damaged.

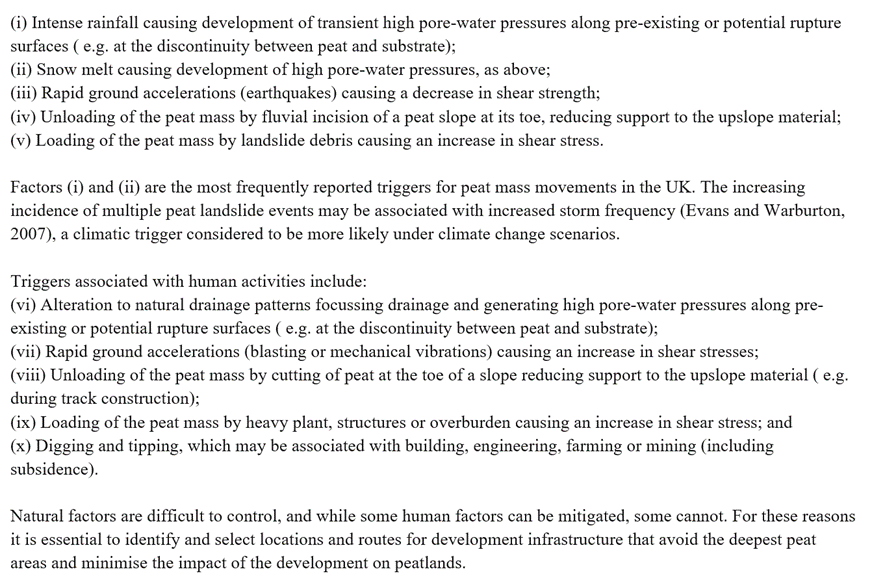

The Scottish government published their Proposed Electrical Generation Development: Peat Landslide Hazard Best Practice Guide in 2017 which contains this section on Triggering Factors.

Richard, a retired geography teacher, his brother Ashley, a retired HGV driver and I discussed all of this as we walked down to the 17th-century Ponden Hall, Thrushcross Grange in Wuthering Heights, with our long circular walk almost complete. Was it at Ponden Hall that the very young Brontës and their helpers sheltered from the storm on 2 September 1824? At Heckmondwike Grammar School in the 1960s I studied this poem by Emily Brontë, said to be influenced by her experience of the bog burst as a child. I feel it more intensely now than I did then.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

This is the 40th in a series of guest blogs originally based on the 65 wind turbines which Richard Bannister planned to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 5, 6, 8, 8CEP, 9, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 21, 21CEP, 25, 25CEP, 27, 31, 32, 33, 33CEP, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 42, 42CEP, 43, 44, 47, 53, 54, 56, 57, 58, 60, 62, 64 and 65 have already been described.

The developers have canned their original 65 wind turbines, quite possibly in response to the public humiliation of having their so-called ‘plan’ publicly shown to be damaging, irrational and probably unlawful. They have come back with a plan for 42 wind turbines and the amazing Nick MacKinnon and friends have regrouped and set off on a new tack too. The series continues.

To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]